Itinerary

To achieve this aim I would have had to use the following methods:

1. engaging a local community through a school or community centre.

2. creating a new artistic language to use in communicating the aims and ambitions of the community.

3. setting up an exhibition with the Architecture Faculty of Moratuwa University for the link between the two communities.

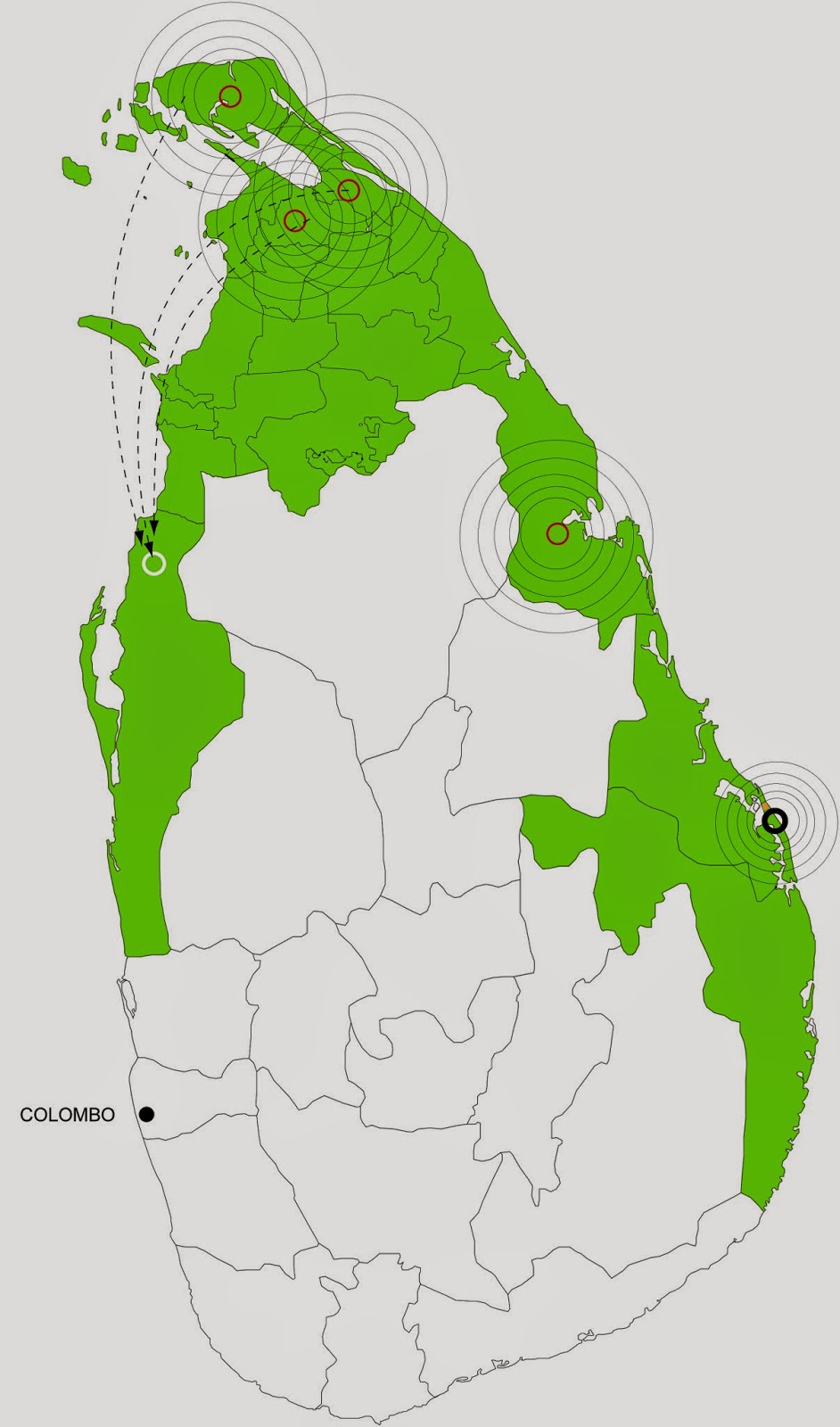

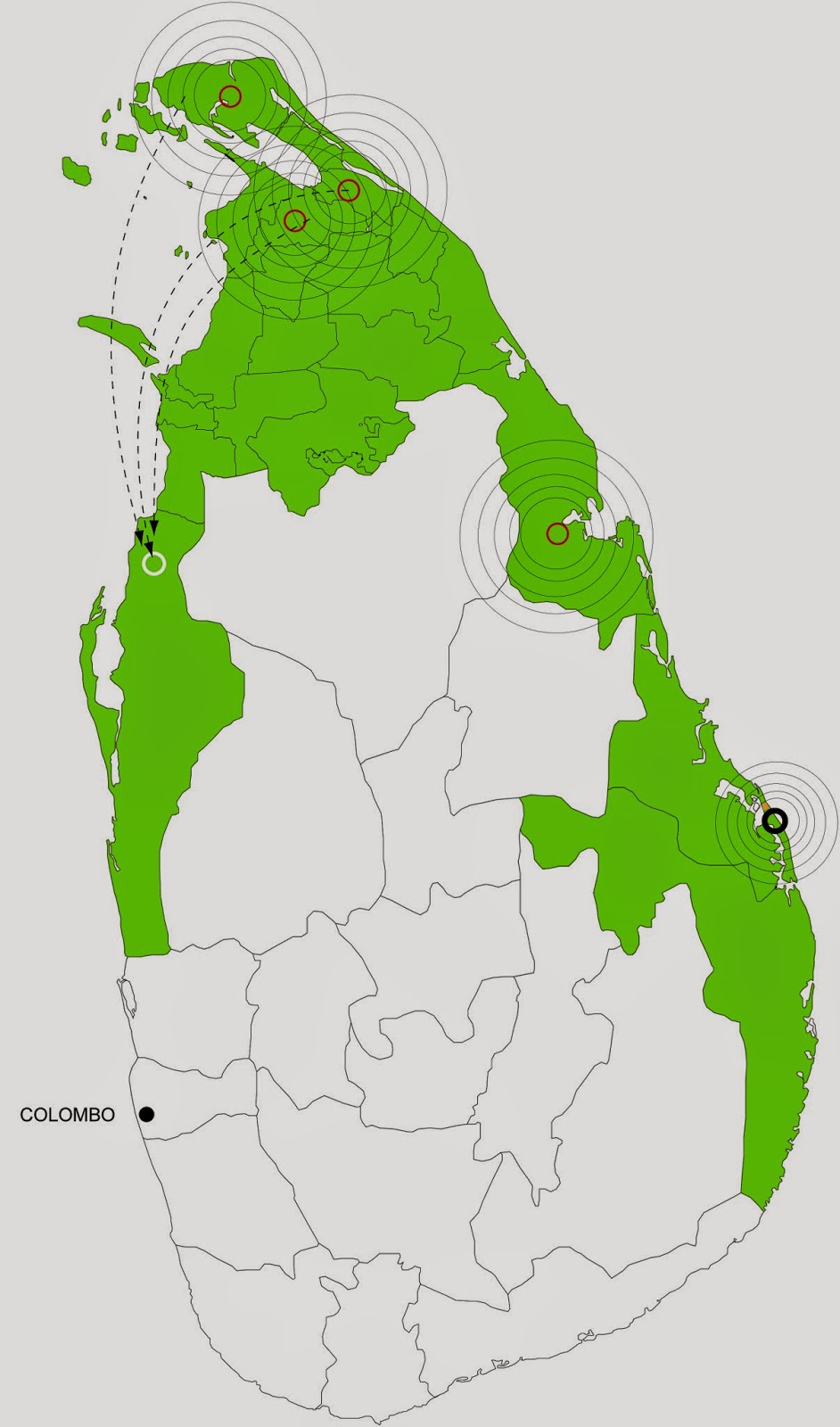

I chose to carry out this research in Colombo, Nuwara Eliya, Batticaloa, and Trincomalee, where a range of natural disasters bind these communities into a dialogue that goes beyond the problem of war, therefore creating the opportunity to re-articulate the debate into a less sensitive subject, whilst still maintaining the same urgency for regeneration. This approach would also allow an ability to gain further access into the hardest hit areas, therefore allowing the research to include post-disaster situations and existing construction techniques into reconstruction.

II. Cultural Background

Pre-Civil War

Sri Lanka was under foreign occupation for over 500 years. In 1948, the new Sri Lankan Government declared Independence from the last of foreign occupation under the British Government. Since then, there have been heated political conflicts over control of the country, mainly between the two majority ethnic groups of Tamil’s (12%) and Sinhalese (78%). These political conflicts escalated to a point in 1983 when a civil war was declared between the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE, a then political party who represented the Tamil minority.

War (1983 – 2009)

During the key periods of conflict during the years 1983-2009, the education system was one of the hardest hit areas of life for most Sri Lankan people. Strikes by teachers and students were commonplace, becoming so serious that it took more than the scheduled number of years to complete a degree. Currently, the number of students admitted for University is at 20,000, where 300,000 sit for their A-Levels. The period of war also reduced the potential economic growth of the country, adding to a general feeling of discontent and frustration amongst the youth population particularly.4

The Northern Province, where the conflict was concentrated, was the “lowest contributor to the national economy” during the 15 year period between 1991 and 2005. Eastern Province was “lowest contributor to national economy in 1990 and between 1991 and 1995”. This period also caused fundamental economic change, where a previously agrarian economy was becoming more expensive and less fruitful due to shelling, and a more service orientated economy became more popular.

Post Civil war (including cease-fire between 2002-2007)

Since the end of the civil war in May 2009, the country has seen high growth, with the country ranked 2nd fastest growing economy in Asia (second to China). New large scale infrastructural projects are being developed, mostly with the aid of foreign investment, and sectors such as Fishing and Agriculture are also on the rise due to freer movement and cultivatable land being made more available.

III. Destinations

The towns I visited were Colombo, Nuwara Eliya, Batticaloa, and Trincomalee. Nuwara Eliya was the centre of the landslide based research, Batticaloa for flooding, and Trincomalee for

Post-Tsunami and coastline tourism research. Due to my experience in Sri Lanka involving

travelling to the varying ethnic demographic area’s of the country, one of the greatest learning impacts was gauging how ethnicity played a large part in daily social life.

One of the first things people would ask me upon striking conversation (or simply attracting attention from my massive backpack) was “are you Tamil or Sinhalese”. I appeared to be either Sinhalese or Tamil depending on where I was (Colombo – Tamil, Batticaloa – Sinhalese). I never took this point of the conversation forward, and never asked “why” establishing my ethnicity before continuing the conversation was so important. I felt it would be better to physically stay entirely away from this subject and focus on the needs based research, and to achieve the physical steps needed to get a holding on the position at which I could make physical difference and change.

Like any largely populated land, or society of different cults, or family of different minds, there is variation in the social fabric of Sri Lanka. To belong to one ethnicity is the first step in gaining access to a cult or sect. Once in, there is the question of language, and this gains you one more level of access. Then there is the question of types of food consumed, prayer and religion, and again, more barriers knocked down for access. And then the belief’s for right or wrong, or one’s affinity to a particular aspect of the faith, for example higher focus on education and knowledge, or the excelling in governance and community etc.

Class

Tension from the furthering distance between rich and poor was a striking visual reality.

Having visited Sri Lanka several times in the last 4 years, I have witnessed elements of the class structure and its representation within the public and private realm. Interesting juxtapositions raise questions about how the collective society is working and developing, especially in this post-war climate.

There are examples in the city where differences in wellbeing and earning capacity are quite clear, for example in the image above. Telecommunications company’s dominate the business spectrum in Sri Lanka, and can be seen tagging small poorly maintained grocery stores like this one all across the town.

Multiculturalism

There is an overriding feeling of equality. Happiness for end of war. Reduced fear of suicide attacks, growing comfort in the public. Presence of military around different areas reduces full public freedoms, yet reassure some of the security they can rely on.

Having spoken with many people in Colombo, it is safe to say that collectively people are positive minded since the end of the war, and are looking forward to greater opportunities that the country can offer them. Evidence of flamboyant spending and a growing night-club industry suggest a growing middle-upper class populating the city centre, where the usual pattern of the University students studying and working abroad is changing, to now studying in higher education and working in Sri Lanka itself.

Whilst this part of society is growing and developing, there are still signs of restrictions to democracy, where military still keep checkpoints and guard off areas of the city if a particular function involves significant members of the state. An example is near key hotels in the city, and especially near the World Trade Centre’s and Parliament building. These locations are heavily policed and a 24/7 military presence is normal. Key roads that lead to the city’s biggest landmarks (Old Parliament square especially) also are controlled, where a different governance strategy is enforced for different times of the day.

Regarding religious representation within the city of Colombo, it is clear that Buddhism overrides any other, where Stupa monuments dot the city landscape, and Hindu Temple’s and monuments are incredibly rare and Mosque’s and Churches are extremely infrequent. Even within many public spaces, such as the shopping mall, internet café’s, or Banks, there will be some form of religious representation. To tie in with this landscape of imagery, the idolized image of Mahinda Rajapaksa, incumbent President of Sri Lanka, sits in sometimes the same locations as the religious imagery, and also in places one would not expect, such as Barber shops, Telecoms stores, and restaurants. His idolisation can be attributed to his role in the ‘crushing of the tiger’s’, where the public euphoria could be paralleled with the American reaction to the killing of Osama Bin Laden.

Nuwara Eliya

Nuwara Eliya as a town can be experienced in two ways: 1. as a silent observer, appreciating the colonial history of houses, hotels, golf club, and tea estates, or 2. as the British mascot, getting complementary beers, becoming a tourism advisor for England, and being regularly passed onto your hotel owner’s sister’s husband’s friends who are around for a short visit and would like to learn about British education and society over tea. Both fortunately did not distract me from my aims (maybe the free tea!).

My aim here was to study the affect’s of recent landslides in the region, and how government were aiding in reconstruction efforts. The reason for this type of investigation was to gain insights into Sri Lanka construction methodology, which would aid my own efforts when conducting my design project later on. The site’s I visited were ‘Mahuwa Tea Estate’, where significant damage was reported on one of the fields, also damaging workers quarters, and ‘Liddlesdale Tea Estate’, where there were reports of grave damage to the estate infrastructure, as well as further damage to roads. Gaining information of locations was possible through visiting the regional DMC (Disaster Mitigation Centre).

Gaining access to the estate site’s however was a challenge, as these are notoriously difficult areas for non-workers/ foreigners to walk in uninvited. However, armed with my research agenda, I managed to gain a meeting with the Mahuwa Tea Estate manager, who then helped provide access to Liddlesdale Tea Estate. Upon visiting the site, I was escorted around by the site manager, who was most helpful in providing relevant information about the damage caused, such as hectares of land lost (9ha out of a total land area of 15ha), the equivalent financial damage (2million Rs.), but when quizzed about government’s aid in reconstruction, he was incredibly hesitant. This fear of commenting on government would reoccur frequently during my visit, and being well acquainted with their history, I am not surprised.

Batticaloa

Batticaloa’s recent history is shrouded in suffering, where human atrocities, direct combat in the town, and the resultant downturn in economy have all taken their toll. The key atrocities that bear their greatest marks are two massacres that affected two different communities: 1. Eastern University student massacre ([DATE]), where University students, teachers, and local’s searching for shelter, were killed en masse by the Governmental Armed Forces; 2. Kattankudy Mosque massacre (1990), where sheltering and praying Muslim Tamils in Kattankudy were shot en mass in two Mosque’s during a LTTE pogrom against the Muslim Tamils to eradicate them from the eastern region (an area they claimed to be part of their Eelam – see map). These atrocities, especially that between the Tamil Muslim moors and LTTE, have left a mark on the social cohesion within the town of Kattankudy, where a multicultural mixed fabric once survived, now left with isolated dense communities of Tamil Muslims and other Tamil’s (Hindu, Christian, other).

Attitudes toward the Government Armed Forces also are negative, escalated by recent reporting of sexual and physical assault by people being identified by the community as military personnel. This additional tension is very dangerous, where wrongfully accused people are being lynched by communities taking law into their own hands. During my visit, due to being a new person within the community and my appearance resembling that of an army personnel off duty, I became a suspect amongst the locals. This suspicion resulted in myself being followed in public, but ultimately as I spent more time in the public domain conducting research and speaking with people, this theory of theirs was soon quashed.

This issue of public paranoia was raised again during my stay in Batticaloa, when after a few days in the town, a (suspected) surveillance individual made contact with myself posing as an advisor to a national organisation. This suspicion (now of mine) was soon removed due to conducting some back checks of my own, but my experience of this paranoia gave an insight of how fear or suspicion is so damaging to a persons/ nations development. Due to my fear of my own safety, I could not work for an entire day, showing that fear is a tactic in itself, and to encourage people to begin expressing outside of these boundaries became an aim for my workshops and later project.

Trincomalee

Trincomalee currently does not display clear signs of the regeneration promised after the Boxing Day Tsunami in 2004, but the hotels that were damaged have now resurrected into incredibly expensive high market buildings within the town. Two key examples are ‘Chaaya Blu’, and ‘Lotus Hotel’, where prices per night start at roughly 13,000 Rs/ (£70.00), which can be compared to an ordinary hotel per night stay of 1,000 Rs. The beachfront boasts globally competitive snorkelling and diving experiences, otherwise very little development is evident along the coastline. It may be the case that people are not ready to re-invest in the coastline because of how devastating another natural disaster could be.

Regarding conducting the planned workshops with local schools in Trincomalee, I was faced with another issue of trust and miscommunication having organised arrangements while in the UK. The school I was scheduled to have a workshop with was ‘Trincomalee Hindu School’, where I had discussed a workshop with the headmaster over the phone in London. Having arrived to Sri Lanka, communication with the school ceased, and the prospect of the workshop rapidly reduced until it was officially declared not possible by the school. This may be because of the fact I had no research prospects for Trincomalee itself (research was concentrated in Batticaloa and Nuwara Eliya), therefore not providing enough incentive for the local school’s participation (this is comparable with Batticaloa where school participation was very quick, perhaps due to the research being directed at local regeneration and improvement).

IV. Workshops

In Batticaloa specifically, my ability to conduct research independently was hampered by paranoia of people recovering from the trauma, very different from the feeling in Colombo as described earlier. The greatest impact that this culture had on my work was my ability to photograph in public, especially of people and public activity. I did not want to raise concern or unnecessary suspicion of who I was and what I was doing, as I did not have immediate family or close contacts with or close to me except for in Colombo. Simply looking at specific events or scenarios, remembering the important details, and drawing out the result in the evening, became the tactic for recording information from the public realm.

On the larger scale, my tactics for movement and access followed three basic points:

- Education:

- Batticaloa Hindu College Workshop

- Kattankudy Community Workshop

- Infrastructure

- Researching directly into waste management and water drainage

- Testing on-site to prove commitment

- Art

- Use to communicate immediate ideas

Workshops

The use of education, infrastructure, and art, were key tools to develop relations and place myself within the context of the Sri Lankan people and their fundamental needs. This meant I did not discriminate a particular demographic in the developments and therefore information I was trying to research.

With education, I used the realm of learning to develop and test ideas with students first hand, within the context of the existing syllabus. The forum of school as space for innovation and ambition was critical to addressing the question of local change. The history of school in Sri Lanka made the interaction far more poignant, where the conflict has directly reduced social mobility through school closure and slower operation, and past massacres have also included those carried out within schools. Regarding how the school wanted to get involved – this was brilliant. We sat for one meeting with the headmaster and senior teacher, and spent 1 hour discussing the relevance of such a workshop of discussing regeneration of Batticaloa, which teachers should be present, whether a translator is needed, what the aim is etc. At no point did the school ask “so what’s in it for us?”. This point was incredibly humbling, and made the topic of simply ‘improving the local area’ the sole purpose of our actions.

Batticaloa Hindu College

Regarding organising the work with the schools, my initial aim was to arrange all meetings and workshops prior to arriving in Sri Lanka, therefore allowing myself to be fully prepared and more economical in making progress. This plan did not work out, due to the people I spoke with not wishing to continue any dialogue related to social improvement over the phone and email. Some school’s questioned whether I was who I said I was, how did I hear about the school, whether what I was doing was legal, and the same painful question of my ethnicity. There was a clear trust barrier, and this therefore impounded greatly on me having to improvise when in Sri Lanka to achieve the best output in the time I had. When actually in Sri Lanka, armed with a list of every school in the regions I was visiting, I spoke to them expressing that I was now in Sri Lanka and ready for business. Having met with the school headmaster’s or teacher representatives for Batticaloa Hindu College and Central College Kattankudy, it was possible to be more expressive and persuasive to finally organise the actual workshop. This dialogue continued as my stay in Sri Lanka continued, therefore developing a rapport, and keeping a blog to update other developments which referenced the workshops and how it fitted into the greater picture of my project research. The feeling of being part of this ‘greater picture’ was what I think attracted the school’s on the ground, and the proposals for workshops would be jointly beneficial for both myself and the students.

For the actual workshops, due to me not knowing the language, I was aided by a translator. These translators, and there are more than one thinks in the small towns of Sri Lanka, usually come from having worked with an NGO during the conflict, where local people were needed with local knowledge and language skills. I met with my translator before the workshop to discuss how we would carry out the class, and this helped in building trust between us both, which helped in class when we needed to work harder to gain what was required from the participants. The questions we posed during the workshop were:

1. What are your aims and ambitions?

2. If there was one thing you could do to improve your area, what would it be?

3. Inject 3 new buildings/ functions into your town – in groups, with a short presentation afterwards

In between, I gave presentations outlining the current status of Batticaloa (recuring floods, growing fishery economy, peaceful paradise to live), and including case studies of towns that had undergone similar transformation through considerable effort and teamwork.

Following this first school workshop, I felt the need to prove that I was serious about my efforts in answering their queries and inputs. Having limited resources, I could of course not make built solutions, but with my pencil and paper I could immediately visualise what they had described as ideas for change and local regenerative improvement:

In addition to these immediate visualizations, I wanted to make a physical intervention in the town, where people could see I could make interventions at the town scale and with partnership of the local Urban Council. This manifested itself in introducing 3 new public bins along ‘Main Street’, where the majority of public waste currently collects in the drainage canals.

These bins were left for several days, with progress of their being used tracked to see if any improvements were evident:

What I found most interesting in this situation was how each retail owner really supported this new intervention, especially when finding out that the local Urban Council were keen maintaining them. They appreciated the effort being put into improving things from the ground up, literally, and this news was well received by the students of the school (my main aim).

Kattankudy Community Workshop

This workshop was organised alongside one of the local teachers and community leaders, Mohamed Jawahir. It was advertised around the town after the bin intervention, with posters being put up around local shops to attract attention:

The actual workshop attracted a variety of locals – Lawyers, journalists, and local Federation of Kattankudy Mosque’s representatives. The group were asked the same questions as the school class, and the same process of drawing over images of existing issues was carried out:

Responses during the workshop were predictably timid, where culturally it seemed difficult for one to talk openly about their personal ambitions and how they fitted into their home town. We were more productive when engaging directly with the city with the printed maps – this overlaying criticism again was far more successful in gaining results that talked about what needed improvement in the town.

V. Conclusion and Next Step

In Conclusion, I managed to achieve the large part of my initial aims, which were to engage a community in a process of cultural regeneration that could potential spark links between UK and Sri Lanka. With regards to technique, discussions around improvement from landslide and flooding damage gave me an over arching practical concern which all residents could relate to and understand, therefore being the most successful tool for communication. These core topics allowed me to access the hardest hit areas, and speak with member’s of the community who could make larger changes quicker, such as local politicians, government organization’s, and land owners of affected land. When approaching the tea estate affected area’s, it was paramount to engage the estate owners, who are significant figures in the estate town’s, and the topic of infrastructural improvement aided in gaining access.

In general, art was the least successful medium of communication within the community, where after consultation and analysis, I produced vision drawings for the purpose of a general discussion of what the new future could look like. Upon presenting these visions and diagrams, those I would present to would become less enthusiastic about the concept and topic of discussion we just had. This change in mood could be attributed to the fact I was creating an image of what the place could be therefore replacing their own vision of the potential outcome. Or it could be part of a social stigma against artistic production outside the realm of religion. An additional note is that all who I spoke with were not interested in ‘well-being’ or comfort, but were more concerned with larger scaled improvements such as those listed above. The bigger infrastructural changes were more prevalent, and therefore overpowered any thought’s about well being in one’s daily life. Due to religion also condoning sacrifice in one’s life, it was not a surprise that better working or living conditions were not being pushed for, especially in the context of a post-war situation where well being was all but thrown out of the window.

The experience and process has lead onto three new schemes: Book Donation Scheme; an Online Consultation Model; and a Book Publishing Centre design project in Kattankudy, Batticaloa.

Book Donation Scheme

Whilst conducting the workshop, and speaking with members from each school in Batticaloa, it was made clear that there were aspirations to create a greater link between themselves and London schools. Ideas about partnering with a UK school was expressed, but I understood this as being slightly outside of my remit as an Architecture student. However, I was interested in developing a relationship that could be regenerative. The solution to this potential scheme would need to deal with the following issues:

- developing links between Batticaloa and London

- aid cultural development

- improve educational potential of the local schools

- become part of a new enterprise

Initial thoughts were around the idea of a book donation scheme, where books could be sent from the UK by ship to Colombo, where they would be transported to Batticaloa and given to schools within the scheme. This would aid cultural development, and allow a process of reviewing the existing books in the Batticaloa schools.

It could also result in the creation of a new area of the existing public library to house these new books, where schools have special access, and potential newly built rooms can provide study spaces especially for the school students.

Online Consultation Model

One of the ambitions of my research was to find a new avenue of intervention, where I could play a part in the cultural regeneration of Sri Lanka. Having experienced the processes that worked and were ongoing for improvement, one of the biggest areas in need of change was one’s ability toward free speech. Increasing censorship with internet news websites, including increased political involvement with printed press, was setting a poor situation for democracy. An idea to combat this in a fair and productive way, was to encourage our current process of getting locals to comment directly about their town (something I did in our town and school workshop). A result of this thinking was to formulate an online version of this consultation, except allowing all people who could access the internet to make direct contributions. This would later become the ‘Online Consultation model’.

Since arriving in the UK, I have been focussed in turning the research conducted in September into a real project that identifies all of the key problems raised during the trip.

This model aims to encourage site specific comments to be saved to that location, resulting in a density array of information about the town, except all derived from a set of simple questions that vary in their complexity and potential outcome.